Will mining company save or destroy the species named after it?

ALERT member Gopalasamy Reuben Clements tell us about a conservation drama playing out in Malaysia.

In Southeast Asia, the mining of limestone karst -- rugged mountains or pinnacles of limestone that are the remnants of ancient coral reefs -- is big business.

In fact, the entire construction industry would grind to a halt if it wasn’t for a valuable commodity from karsts -- the limestone needed for cement.

Apart from being important sources of groundwater, limestone karsts are also key habitats for certain plant and animal groups that, in turn, provide important ecosystem services for humanity.

In particular, the nectar-feeding Dawn Bat, which is the principal pollinator for fruit-producing durian trees, require limestone caves to roost in.

As limestone karsts disappear across Southeast Asia, so will the bats, and the durian fruits along with them.

The famous durian fruit, much prized in Southeast Asia (photo from www.molluscan.com)

In Peninsular Malaysia, more than 500 limestone karsts are scattered across the landscape. Because of their isolation from one another for millions of years, limestone hills only a few kilometers apart can host unique species found nowhere else on Earth.

It's no wonder that these rugged geological formations are regarded as arks of biodiversity.

A limestone karst (photo by Gopalasamy Reuben Clements)

From one such limestone karst in the state of Perak, Malaysia, I discovered a bizarre snail species in 2008. This snail, Opisthostoma vermiculum, is now the only land snail in the world with four axes of coiling. It was also considered to be one of the top 10 species discovered in 2008.

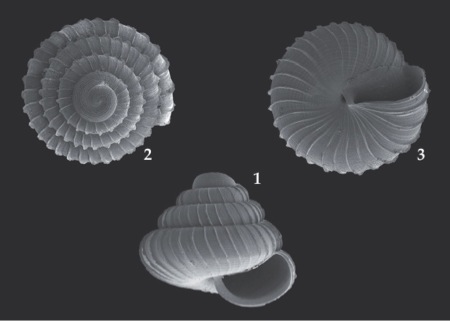

Within the same state in Malaysia, scientists recently discovered a new snail species on another limestone karst, known as Kanthan Hill, that is currently being mined. Aesthetically, the shell of this new species makes less of a statement than O. verimiculum, but it is making a huge statement in conservation circles.

The newly discovered Lafarge snail (from Vermeulen & Marzuki (2014) Basteria 78: 31-34)

The scientists who discovered this snail named it Charopa lafargei, after the international mining company Lafarge that owns the mining concession in which this snail was discovered.

Kanthan limestone hill, home to a number of unique endemic species, including a new snail (photo by Ong Poh Teck/Basteria).

This endemic snail is already threatened with extinction because of Lafarge’s massive quarry. It will soon be listed as a Critically Endangered Species.

Apart from this snail species, Kanthan is also home to nine plant species on Malaysia's Red List of Endangered Plants, one Critically Endangered spider, one gecko, and two other land snails found nowhere else in the world.

Lafarge has undertaken some initial steps to protect the unique Kanthan wildlife, including a biodiversity assessment. This is, however, considered insufficient to secure the future of the endangered fauna and flora found there.

Now there are calls for Lafarge to engage leading international biologists to conduct surveys of plants and animals in and around the quarry, leading to habitat and species management recommendations that are publicly available and peer-reviewed. Till then, quarry expansion should be prohibited.

Beyond this issue, what’s urgently needed is a conservation assessment that ranks limestone karsts in Malaysia according to their suitability for preservation or quarrying. This national-level exercise should consider the biological, geological, economic and cultural importance of each individual hill.

Unfortunately, getting funding for this from industry and government has been extremely tough. But it's an urgent task -- the stakes for some of Southeast Asia's most unique biodiversity could not be higher.