Unconventional-gas mining: Are we grabbing a tiger by the tail?

In Australia, as elsewhere, huge efforts are being focused on exploiting unconventional-gas deposits. Australian ecologist professor Steve Turton explains what it's all about and why it should be making us nervous.

We hear a lot these days about unconventional gas. What is it?

Unconventional gas includes coal-seam gas, shale gas, and tight gas. There's a heck of a lot of it on Earth but it's found in complex geological systems and can be devilishly difficult to extract.

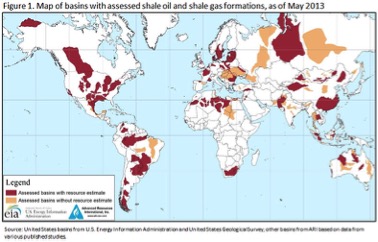

In its 2013 report, the U.S. Energy Administration estimated that recoverable supplies of shale gas totaled some 188 trillion cubic meters worldwide. Known reserves occur in 41 different countries.

And there's a lot of coal-seam gas too -- about 143 trillion cubic meters worldwide, according to a 2006 study.

This sounds like good news for an energy-hungry world, so what's the downside?

For starters, like many forms of mining, unconventional-gas extraction has been implicated in a suite of nasty environmental impacts. Some of these were highlighted in an independent report commissioned by the Australian Council of Environmental Deans and Directors, which focuses largely on coal-seam gas exploitation in Australia.

Why worry about coal-seam gas? For starters, there are major surface impacts, with native vegetation being bulldozed for often-dense networks of roads and drilling platforms. Fragmentation of forests is a common result, with potentially serious impacts on biodiversity.

In farming regions, coal-seam gas operations can have large impacts on agriculture and forestry operations. They can also pollute surface waters and have largely unknown impacts on vital groundwater resources.

Unconventional-gas production often competes with existing land uses, such as agriculture, plantation forestry, and urban areas, leading to heated conflicts among different users. The Lock the Gate Alliance in Australia resulted from a conflict between farmers and coal-seam gas companies. Expect wicked environmental problems to arise for irrigated agriculture and intensive grazing as well.

A big problem is getting rid of dirty water. For coal-seam gas extraction, high-pressure water is pumped into wells to hydraulically crack ("frack") gas-bearing strata, releasing the gas. The gas is pumped to the surface along with a lot of dirty water, salt, and chemicals liberated by the fracking process.

Disposing of all this dirty water is a big problem. Heavy rains can cause containment ponds to overflow, releasing the dirty water into nearby waterways.

Compared with the surface risks of unconventional-gas extraction, we know much less about how groundwater is affected when mining shale gas and coal-seam gas. A key worry is this: Could underground aquifers vital for irrigation and human uses be contaminated?

What is the way forward for unconventional gas? There is little doubt that production of unconventional gas poses a risk to biodiversity and groundwater. We also know the industry often encroaches into high-value landscapes, competing with biodiversity conservation, the production of food and fiber, and sometimes even moving into urban or peri-urban areas.

Because the planet needs energy, it's clear that unconventional gas is not going to go away. Managing its exploration and production will require a holistic landscape approach, taking into account cumulative impacts and strategic assessment frameworks.

Where there are key unknowns –- as often occurs when one is dealing with groundwater –- the precautionary principle should be applied. If we're uncertain about the environmental impacts that might arise, the wisest choice is simply not to drill.

Otherwise the tiger we're desperately trying to hang onto might just turn around and bite us.