Nature Conservation Can't Wait For Economic Development

Environmental journalist Jeremy Hance, a regular contributor to ALERT, highlights an important study with big implications for nature conservation.

There is a terrible irony in conservation today.

The nations that harbor the vast bulk of Earth's biodiversity -- all lesser-developed countries in the tropics -- spend relatively less on protecting nature (as a percentage of their per-capita GDP) than do countries with lower biodiversity.

This lopsided situation means that conservation actions cannot wait for poorer nations to develop economically, as has been stridently argued by some. This is the central thesis of an article in Conservation Biology by researchers Tim McClanahan and Peter Rankin.

Simply put, there is no time to wait, say the authors. Instead, actions in megadiverse countries must be both redoubled and re-evaluated according to each region’s distinct cultural values, if we hope to stave off a mass global extinction.

In megadiversity nations, conservation can't wait -- Yasuni National Park in Ecuador.

Cultural Differences

The authors looked at data for 55 countries and found a distinct cultural split between tropical and temperate nations, based on personal values and social structure.

Nations in temperate regions were more individualistic and autonomous, with stronger government and a greater focus on the long-term. In contrast, societies in tropical nations tended toward group-orientation and formal hierarchies. Tropical governments tend to be weaker and to focus more on the short-term, according to the researchers.

The researchers also found that more individualistic countries with stronger governments spend more on conservation inside their borders, whereas nations with a greater focus on the group and weaker governance doled out less.

The researchers theorize that individually focused countries may support conservation more generously because their focus on individuality extends to the rights of species or life in general. In other words, they tend to think that all species have a right to exist.

Rainforest butterfly in Sumatra, Indonesia (photo (c) Supri Katambe)

There were some exceptions to these trends. For instance, Costa Rica and Thailand spent more per capita than expected given their culture and governance, whereas Germany and Israel spent less than expected.

Still, the general pattern ruled for most countries: collective-focused countries spent relatively less than did individualistic nations on nature conservation.

Culture and Conservation

The authors insist their study shouldn’t be seen as a sign that conservationists should just throw up their hands and admit defeat in the tropics. Instead, it should be seen as a call for changing how conservation is preached and performed in more communally-oriented countries.

First off, they advise that one shouldn’t argue that these countries should just become rich and then they will support conservation.

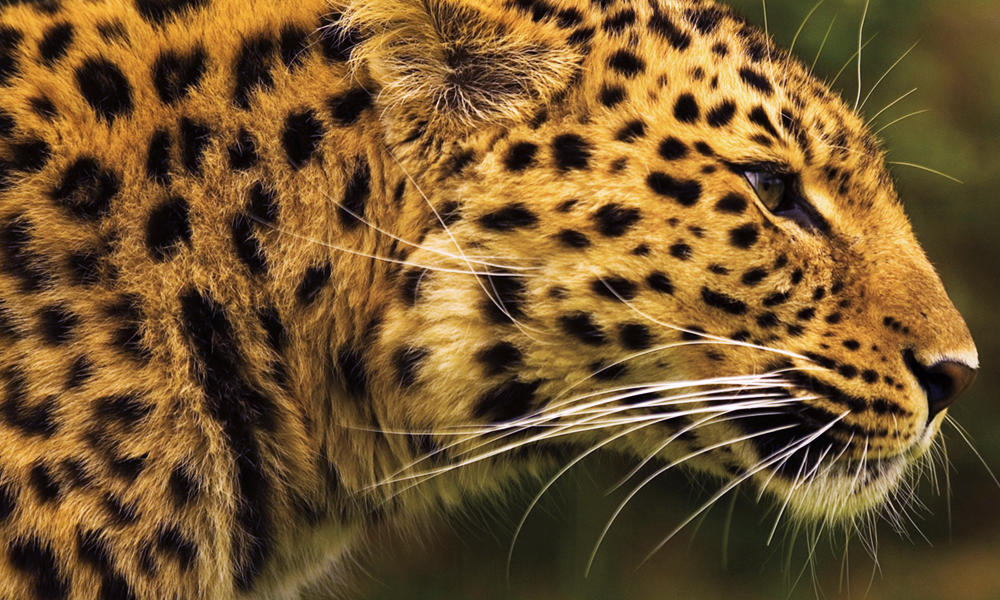

Instead, conservationists might have greater success in tropical nations by focusing on flagship species with special cultural importance to their respective countries, such as tigers, elephants, pandas, and lions.

Iconic species can be great for promoting conservation -- especially in nations with more-collective social systems.

Conservation could be promoted by protecting critical habitats for these species, which need large areas to survive. Of course, non-charismatic species can be left behind if they don’t share the same habitat or are threatened by different factors.

Furthermore, conservationists should target leaders and others high in the social hierarchy to take action. Reaching out to broad groups of stakeholders -- as is often done in individualistic cultures -- may not achieve as much success in communally-oriented cultures.

Getting poorer nations to prioritize conservation more strongly may well depend on viewing the problem through their culture’s eyes.

Pitfalls in the North Too

Of course, wealthier temperate countries have problems of their own.

Many things can trip up conservation actions in individualistic countries. For example, individualism and an obsession with wealth and private property can undercut the capacity of these countries to recognize, protect, and adequately fund conservation.

Furthermore, many wealthier, developed nations have degraded their environments decades ago. Having seen the dire consequences, they have since upped their investments in conservation.

In the end, conservation in both poorer and wealthier nations has its pitfalls. But the key, say the researchers, is to tailor conservation strategies to better fit local cultural values.

The bottom line: There is no "one size fits all" approach for promoting nature conservation.

And perhaps even more important: We simply can't wait for the world to develop economically before we press ahead with conservation initiatives. Such a 'delay-until-tomorrow' strategy is a formula for failure.