Perils growing for Earth's biodiversity hotspots

Biodiversity hotspots are Earth's most biologically important real estate. An important new study -- which you can download free here -- sees dark clouds on the horizon for many these crucial ecosystems.

Where the rare things live...

There are 35 biodiversity hotspots across the planet. They encompass a wide range of different ecosystems but they all have two key features:

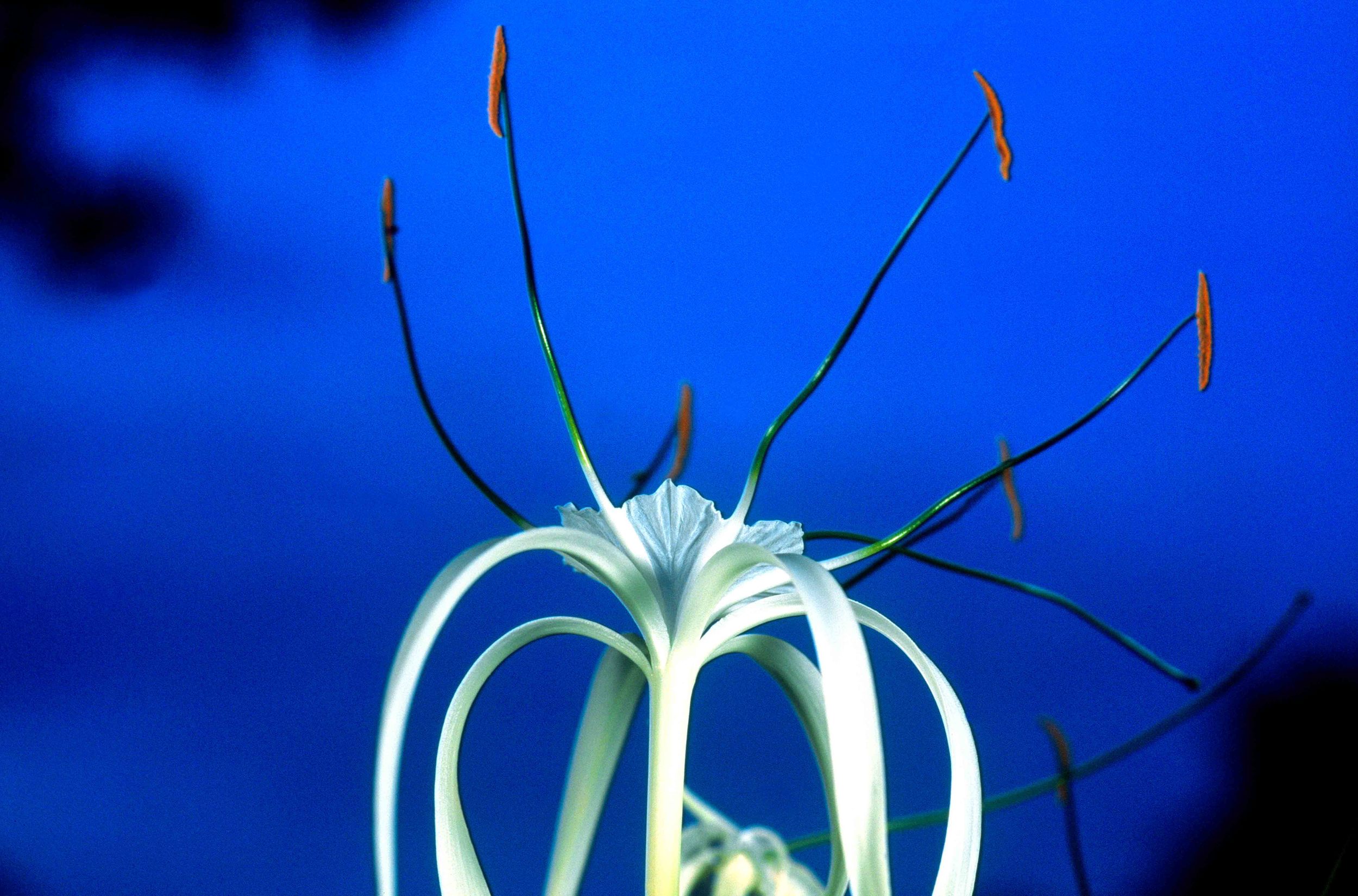

First, they're jam-packed with species, especially those that don't occur anywhere else on Earth. These are known as "locally endemic species" and they're notoriously vulnerable, because they live in just one small area. For instance, the island of Madagascar has lots of species, such as lemurs, that are completely unique to the island.

Second, hotspots, by definition, have been nuked by land-use change: at least 70% of the original vegetation has disappeared.

The new paper, led by geographer Sean Sloan and including ALERT director Bill Laurance, used a rigorous satellite analysis to estimate how much of the original vegetation survives in an intact condition in each hotspot.

Unfortunately, most hotspots have much less intact vegetation than previously estimated. Half now have less than a tenth of their original vegetation -- at which points things start to look seriously dodgy for biodiversity, in part because the original habitat gets severely fragmented and reduced.

An interesting finding is that the hotspots that were formerly in the best shape, in terms of having more of their original vegetation, suffered the worst. Drier habitats, such as dry forests, open woodlands, and grasslands, fared badly, largely because of expanding agriculture.

These findings highlight an important reality. For biodiversity, the Earth is far from homogenous, with certain crucial regions overflowing with rare species. Conserving the last vestiges of these endangered ecosystems is simply vital if we're going to ward off a catastrophic mass-extinction event.