Human Impacts on the Planet are Severe but Slowing Down

The environmental footprint of humanity is massive -- no single species has ever consumed so much of the planet’s energy, resources, and land area.

But thankfully, the pace of expansion of the human footprint appears to be slowing down, at least relative to human numbers and economic growth.

Those are the conclusions of a new study in Nature Communications, led by Oscar Venter and including ALERT members James Watson and Bill Laurance.

Global Footprint

By 1993, humans had significantly altered 77 percent of the planet’s ice-free land area, according to the study, which examined changes in human presence indicated by composite maps of roads and other infrastructure, cities, crops and pastures, electrical night-lights, and other variables.

By 2009, the human footprint had grown to 86 percent of the planet’s land area.

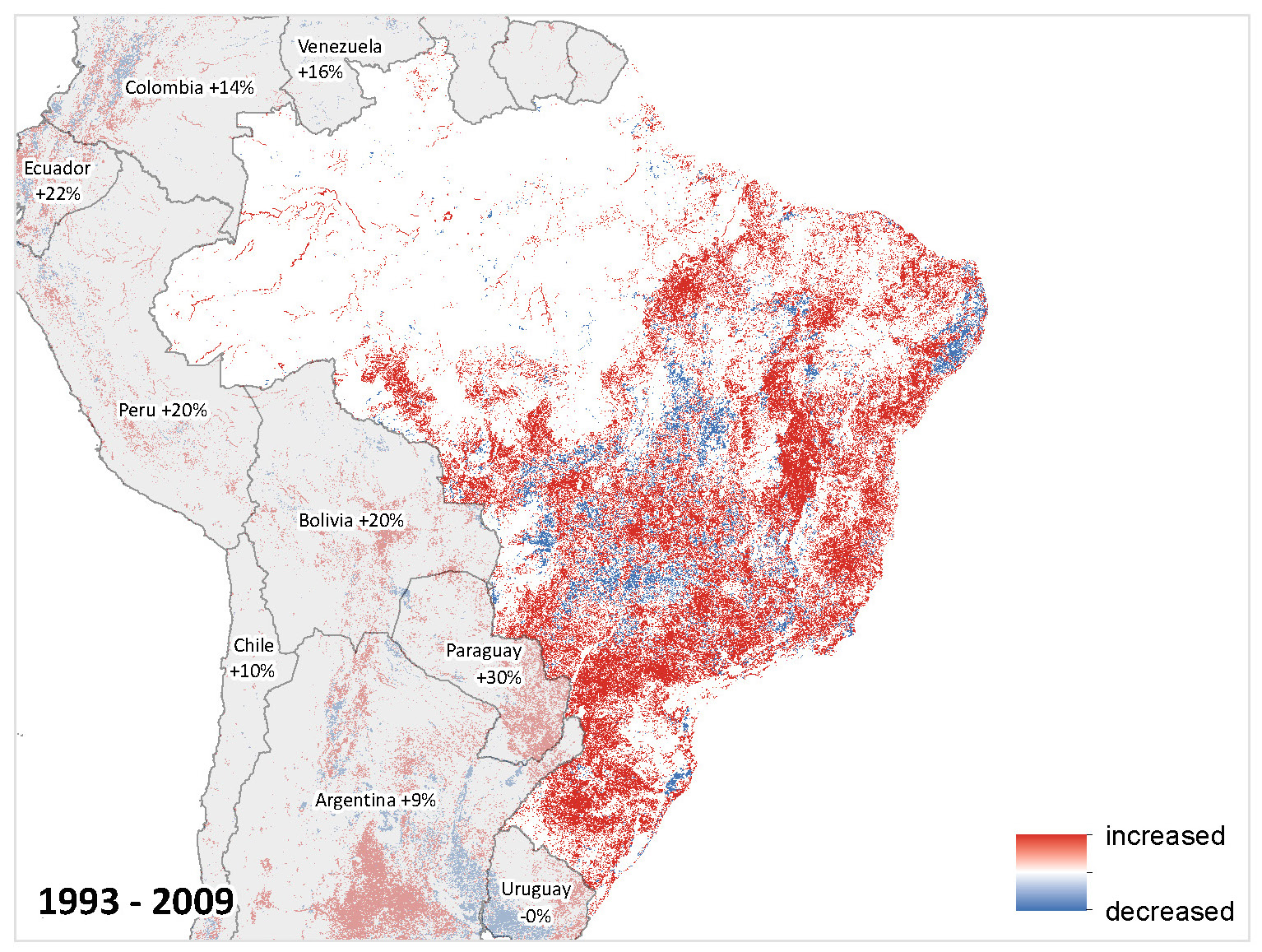

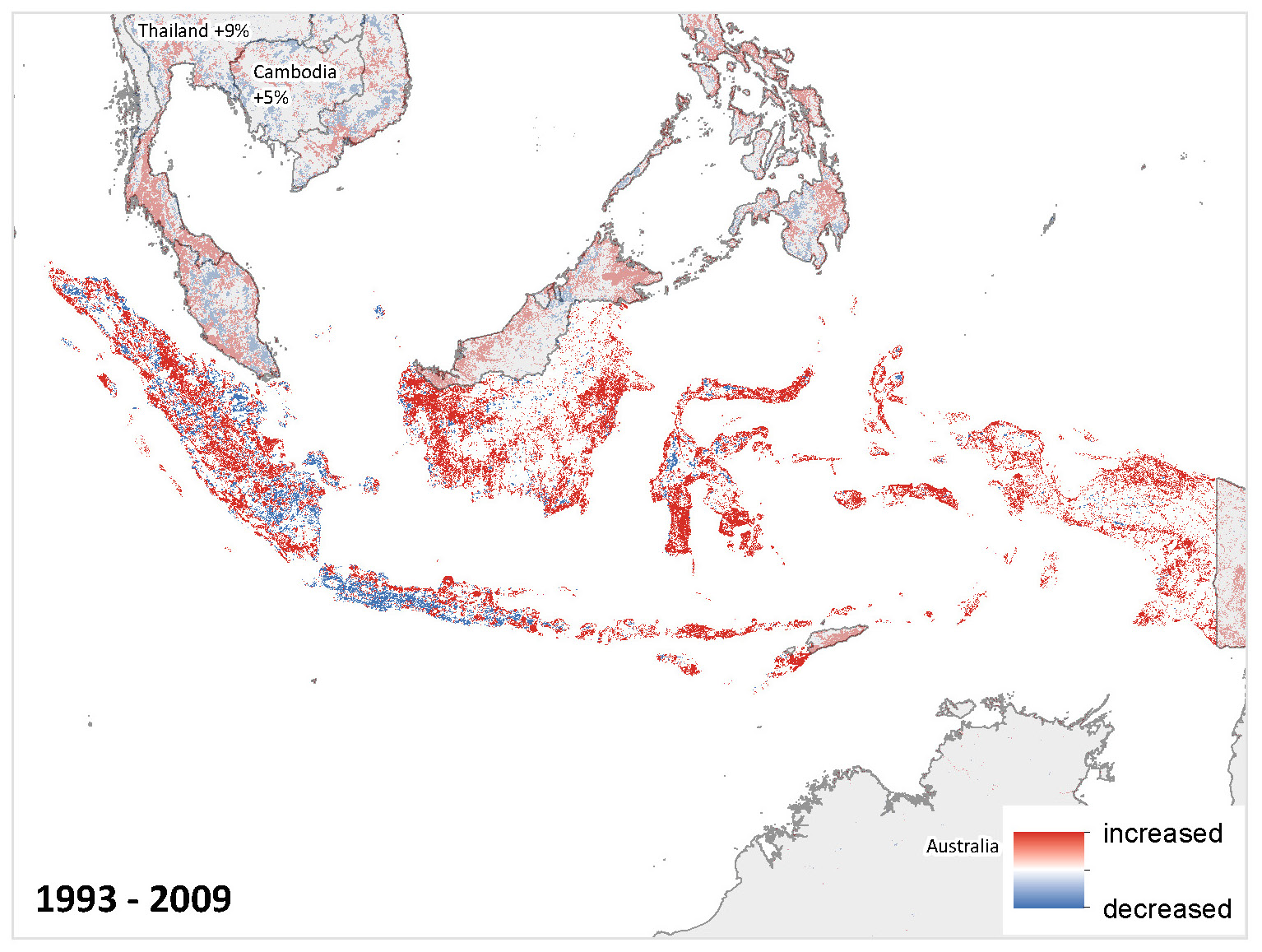

Changes in the human footprint for Brazil (above) and Indonesia (below).

The areas that had been exploited the most heavily were those suitable for agriculture, with arid deserts and chilly boreal regions being least vulnerable.

Furthermore, the most biologically rich and imperiled areas of the planet -- the so-called “biodiversity hotspots” -- have suffered tremendously. Ninety-seven percent of their total area had been heavily altered by 2009.

Silver Lining

These numbers are pretty scary. But there’s another, more optimistic way to look at them.

From 1993 to 2009, the global human footprint rose by just 9 percent. That’s a lot smaller than the growth of the human population -- which rose by 23 percent -- or the expansion of the global economy – which exploded by over 150 percent -- during the same period.

Hence, while human impacts are expanding in many areas and often becoming more intense where they previously occurred, at least -- thank God -- they are not growing at the same breakneck pace as the human population or the global economy.

If that were so, there would barely be a square centimeter of pristine land left on the planet.

Climate Change

An important caveat of the new study is that it looks only at human land uses. The impacts of human-induced climate change are not considered. If they were, it is likely that the entire planet would already be altered in some way.

Still, the study suggests that humans are becoming more efficient in our use of land. That’s surely good news.

There’s not a lot of land left unaffected by humans on Earth. A vital priority is to use the lands we’ve already exploited more efficiently.

For example, across large areas of the planet, farming is inefficient, producing just a fraction of the amount of food per hectare that would be possible with more modern farming methods, fertilizers, and high-yielding plant varieties.

Farming is inefficient across large expanses of the world, especially in developing nations such as this slash-and-burn plot in Madagascar.

We direly need better farming given that global food demand is projected to double by mid-century.

In many other areas, the footprint of cities is growing massively, as poorly planned urban areas sprawl outward and gobble up farmlands and surviving native ecosystems.

And all the while, human infrastructures are penetrating into many of the world’s last wild places. By 2050, for example, it’s projected that we will have 25 million kilometers of new paved roads on Earth -- enough to encircle the planet more than 600 times.

And around nine-tenths of those new roads will be built in developing nations, often in the tropics and subtropics -- which harbor many of the planet’s most biologically diverse and environmentally important ecosystems.

Bottom Line

Even with growing efficiencies, it’s going to be tough to sustain much of our natural world if our population and per-capita consumption keep growing. There are limits to what the planet and nature can bear.

We need to work hard to slow population growth, limit human consumption, and defend our remaining wild places and protected areas. Better land-use planning and enforcement are vital.

So, while the study by Oscar Venter and colleagues suggests there’s light at the end of the tunnel, we’re still a very long way from basking in the sun.